Aurelia Reviews: José María Velasco at the National Gallery

How can we, in 2025 in London, respond to a 19th-century Mexican landscape painter?

José María Velasco, The Great Comet of 1882, (1910), oil on canvas

Firstly, a Couple of Questions For You:

What are the landscapes which embody your idea of home?

Who are the people showing them to the world?

Windows to a Forgotten Time: Teleporting to The Valley of Velasco

Having escaped the bustling entrance hall and reached the sanctuary of this surprisingly quiet exhibition space, my first impression was that of awe. The subtly dim lighting with the paintings gently projected in spotlights, illuminate what seem to be a series of windows. Windows looking onto such dramatic landscapes that they almost feel fantastical – particularly to a Londoner like me. I was experiencing both time travel and teleportation all at once, to the valley of Velasco.

Exhibition of José María Velasco at the National Gallery, June 2025

Whose Eyes Are We Seeing Through?

José María Velasco (1840–1912) was a Mexican landscape painter. He studied at the Academy of San Carlos, learning traditional European techniques. His education expanded his scientific curiosity, exploring botany and geology. Velasco was working in a country experiencing rapid flux in 19th-century Mexico, as it continued to define itself after independence, in an era of political instability and foreign intervention. Velasco used expansive vistas as a celebration of nationhood with a distinctively Mexican voice. Flooded with symbolic references, his paintings make monuments from mountains.

Hidden within the mass of each volcano and the fog of each cloud, Velasco doesn’t just depict a landscape, but a nation that was rapidly changing.

At a time when Mexico was re-shaping its modern identity, Velasco used his work as a vehicle to represent personal and collective memory, but also to express the potential of the future. The tension between poignant nostalgia for rustic living and the fascination for industrial developments, generate a uniquely conflicting mood. I felt a bittersweet kind of hopefulness evoked.

Climate Activist or Scientist?

Climate change is a topic now frequently explored in art galleries. However, Velasco was already documenting the disappearing world ahead of his time and capturing a pivotal turning point in human history. His landscapes are everything from the subtly romantic, to the sublime, but they are also recording the fragility of nature under human domination. One can sense another duality here – between the sublime power of nature and the disruptive power of human science. In my opinion, the power of nature overpowers that of the human in his work, in which he places more weight and drama within the natural forms than in the man-made elements, which always look a bit puny in their dramatic environments.

José María Velasco, The Textile Mill of La Carolina, Puebla, (1887), oil on canvas

Velasco’s scientific passion is a fascinating (and often underplayed) dimension of his practise. He wasn’t only painting his subjects, but studying, documenting and classifying them, in a manner which synthesised fine art with natural science. Velasco's mountains and volcanoes, such as those in his iconic views of Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl, are rendered with surprising geological accuracy. He depicted the land not as an aesthetic background, but as a living ecosystem with its own importance and narrative. His knowledge of Mexican terrain was so accurate that geographers have even used his paintings as historical records of the local environment! His study also encompassed native flora, which were, of course, botanically precise.

He used these natural elements intentionally and symbolically, with the same potency as figurative additions. Therefore, Velasco’s environmental subjects weren’t simply decorative but unquestionably political. Within the narrative of Velasco’s Mexico, he actively elevates the Mexican landscape as a way of bolstering national identity and continuity through his connection with nature.

Why London, Why Now?

In my opinion, Velasco's landscapes don’t passively hang on the wall, but they quietly disrupt it. In a gallery which has been historically dominated by European perspectives, Velasco’s work reflects a broader reckoning within major art institutions by claiming a kind of status and fame which only now is possible in this setting. I had never heard of José María Velasco until this week, and I cannot believe that he is not a more widely recognised name in Europe. This exhibition was not curated to portray Velasco as an ‘exotic’ artist with alien subject matter, but to demonstrate how relatable his work is to all of us.

Velasco’s landscapes, painted in the shadow of colonial legacy, now hang in London – a somewhat charged setting, with the city’s history rooted in empire. Now housed within the austere walls of one of a traditional institution, his pieces contribute to a thoughtful exchange.

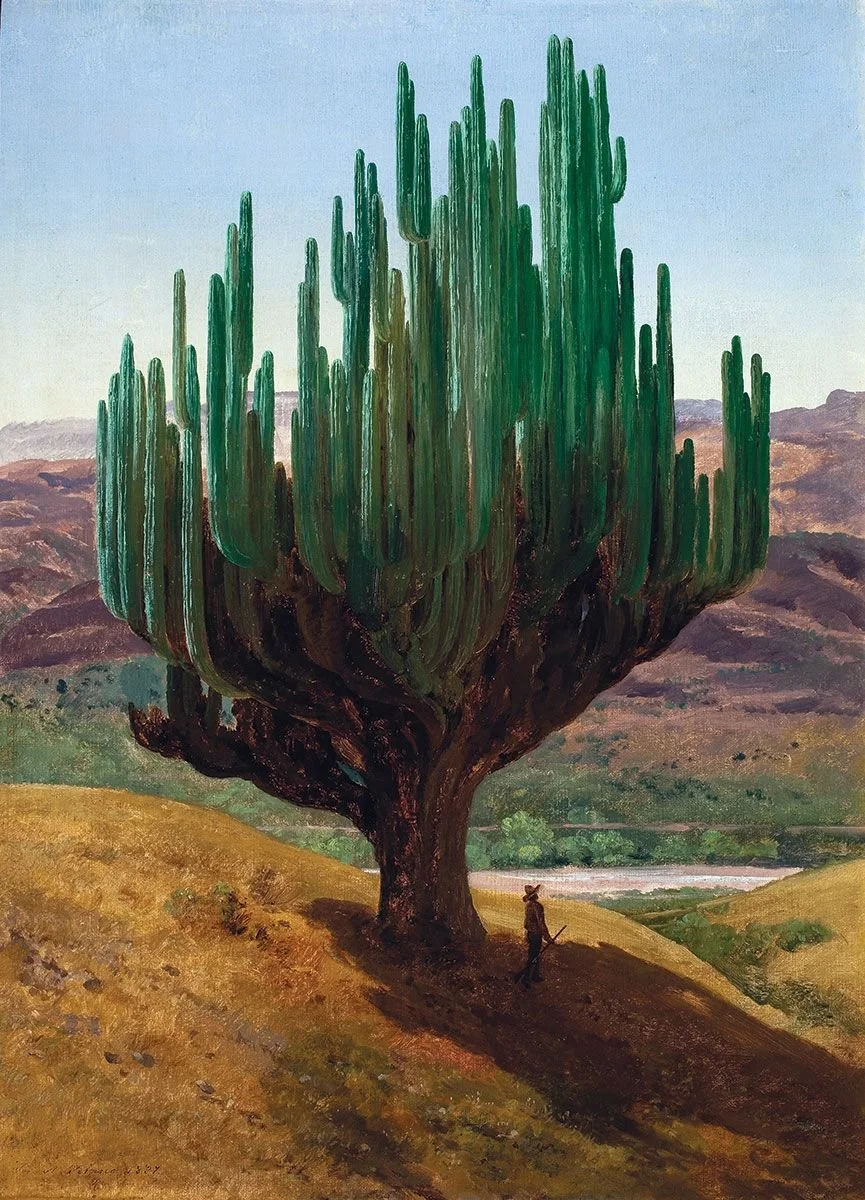

José María Velasco, Cardón, (1887) oil on canvas

Agave: More Than Just a Sweet Nectar

The agave in the foreground of The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel (1875), resonates beyond its compositional value and holds symbolic significance. The distinctively Mexican plant reflects themes of national pride, whilst also demonstrating resilience and the ability to survive in tough terrains – hardy and unyielding. It is anchored to the earth despite what other transformations may happen around it. It appears so small in contrast to the expansive valley, with our eyes naturally pulled towards the centre of the painting and the vanishing point in the horizon. Despite this, its spiny frame still stands firmly in its place, near to us.

Encountering this little agave plant now in London, we are reminded of its enduring, native presence. There are no bells and whistles, no austerity or grandeur to match the institutional setting it now finds itself in. Its anchored nature actually feels at odds with the migration of the physical painting and its displacement to an alien context. I think this juxtaposition only enhances the original message and highlights it more clearly. It’s as though, we as viewers, observe the scene almost as a potential threat to the peace and harmony. However, I find myself coming to the conclusion that change is inevitable. As much as that agave wanted to remain rooted in its territory, it made its way across the globe, and even over oceans to unfamiliar terrain – not from an act of violence but from an act of celebration and reflection. As much as we must preserve national identity and pride, we must also encourage and celebrate transnational modes of thinking. Collaborations and dialogues across continents and across cultures is the best way for us to grow and understand more about ourselves.

José María Velasco, The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel, (1875), oil on canvas

Back to You:

Facing Velasco’s sweeping vistas, my mind drifted beyond Mexico, and to the landscapes that I find familiar and significant. In a modern world of excess screentime and dopamine addiction, showing us hundreds of different locations (some not even real ones) every single day, I feel an urge to reconnect with those fundamental anchors of personal identity. For me, connecting to my environment also comes through my art. Like Velasco, I find myself reckoning with questions of climate change and technological development. I even think of globalisation and tourism and how this transforms physical and non-physical landscapes.

Let’s remember the questions we started with. How do you answer those questions now, having visited the Valley of Velsaco?

Exhibition is open until the 17th August 2025 at the National Gallery, London.