Aurelia Reviews: Kiefer / Van Gogh at the Royal Academy

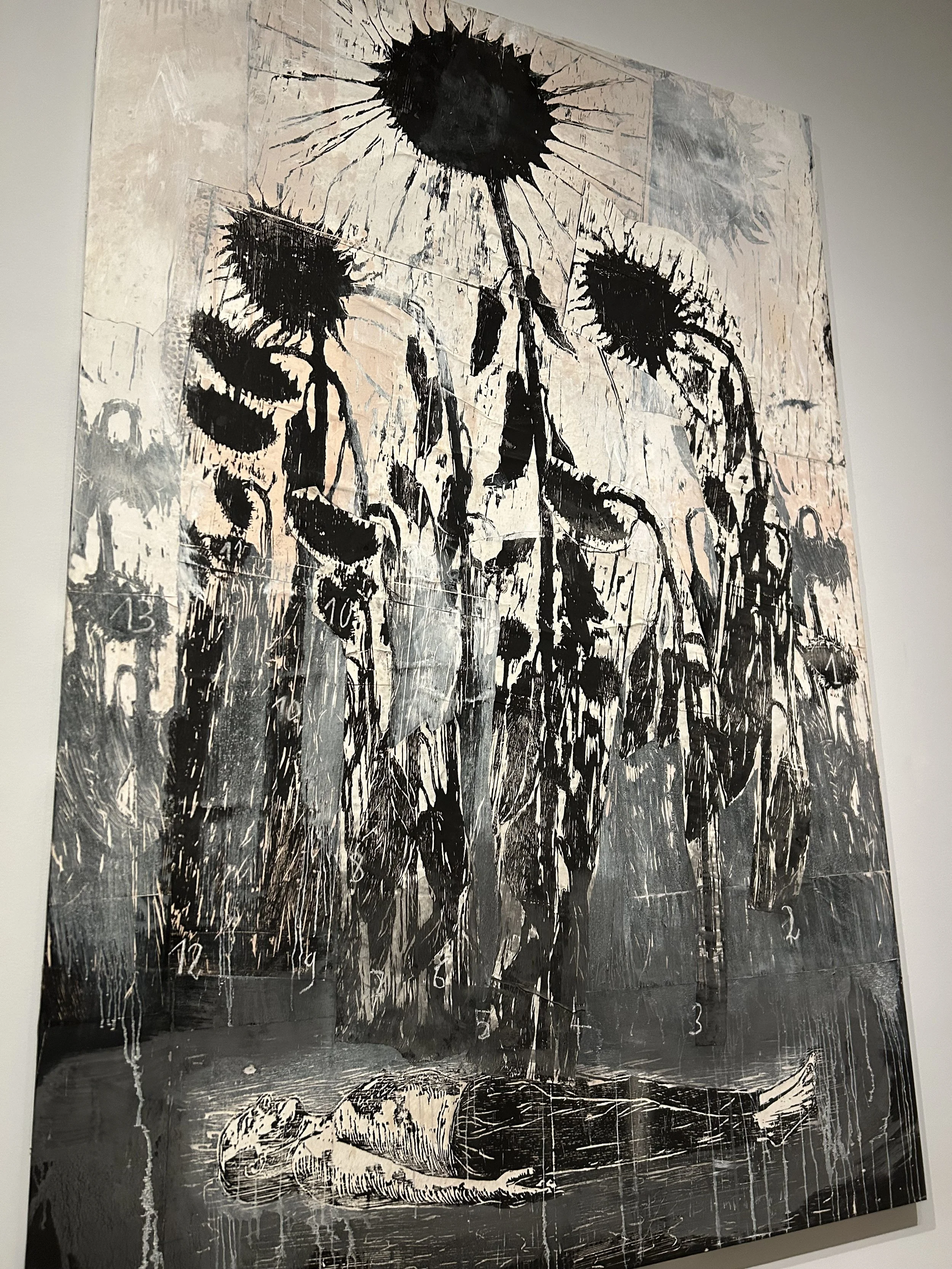

Anselm Kiefer, Sunflowers, (1996), Woodcut, shellac, and acrylic on canvas

What if Van Gogh had lived to witness the 20th century’s descent into fire and steel? Would his landscapes have the apocalyptic devastation of Kiefer’s?

Over seven decades after Vincent van Gogh’s final years, Anselm Kiefer travelled to Provence to understand the landscape of an artist he greatly admired. This is a particularly focused curatorial exercise exploring both Van Gogh’s influence on Kiefer and the way in which a posthumous dialogue can take place between their works – including with new pieces by Kiefer which are on display for the first time

Hanging in one of the smaller exhibition spaces, The Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries, one can connect with the work on a more intimate level, particularly as the scale of Kiefer’s work is so enormous and immersive. The more tucked away location within the RA building is also a pleasant contrast to other showstopper exhibitions.

A Stark Contrast – Is This Really the Same Place?

In this bold pairing of Vincent van Gogh and Anselm Kiefer, we are invited to imagine what Van Gogh’s already troubled soul might have conjured in the scorched landscapes of post-war Europe, had he not been tempered by the sunlit fields of 19th century Arles.

Kiefer’s pieces do not reflect the same visions of Van Gogh, despite the locational similarity. Instead, they show the more human side of our landscapes and how we can poison the land. In fact, they demonstrate a vicious cycle, because these desolate fields reflect the sickness of contemporary nations, wounded and healing from war. What was once a place filled with life, as seen in Van Gogh’s paintings, became one absent of life. Murders of crows are often the only sources of vitality.

Anselm Kiefer, Nevermore, (2014), Emulsion, oil, acrylic, shellac, gold leaf and sediment of electrolysis on canvas

Vincent Van Gogh, Snow-Covered Field with a Harrow, (1890), Oil on canvas

Private vs Public

Living at only the verge of modernity, Van Gogh channelled his personal anguish into an almost spiritual engagement with nature and light. His works were not painted with the intention of being widely seen. Van Gogh was haunted by his own demons, feeling intense highs and intense lows, and using his art as a form of grappling with his own experience. Painting was an obsession for him. He was not respected in his lifetime and was not concerned with the politics of what he was making. Kiefer, working in the 20th century and in a world that celebrates ‘the artist’. As a respected figure, he created his works as a form of political activism: these pieces are meant to be seen and reflected upon.

Anselm Kiefer, Walther von der Vogelweide: Under the Lime Tree on the Heather, (2014), Emulsion, oil, acrylic, shellac, gold leaf, sediment of electrolysis and charcoal on canvas.

Vincent Van Gogh, Poppy Field, (1890), Oil on canvas

Two men in dialogue?

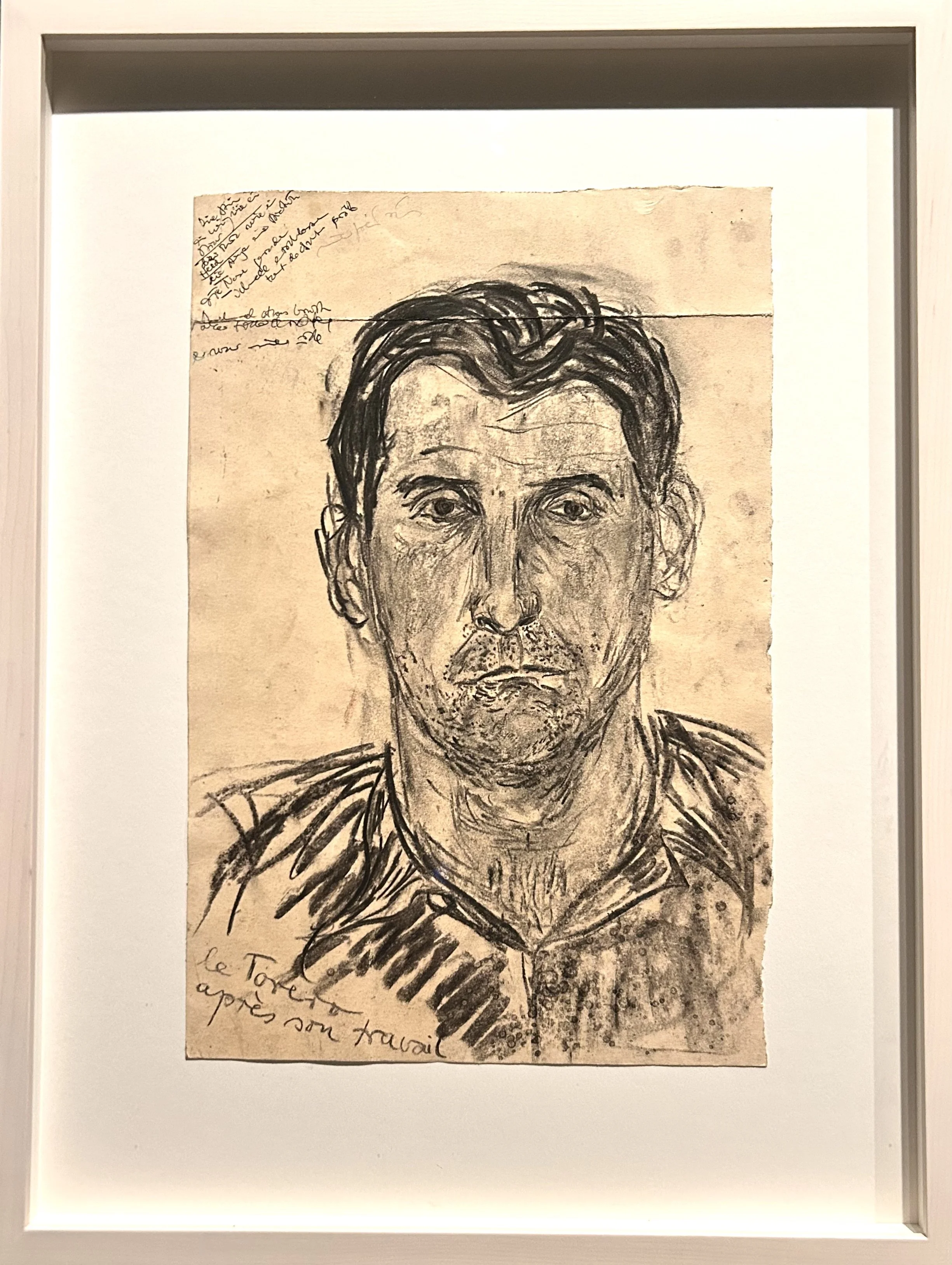

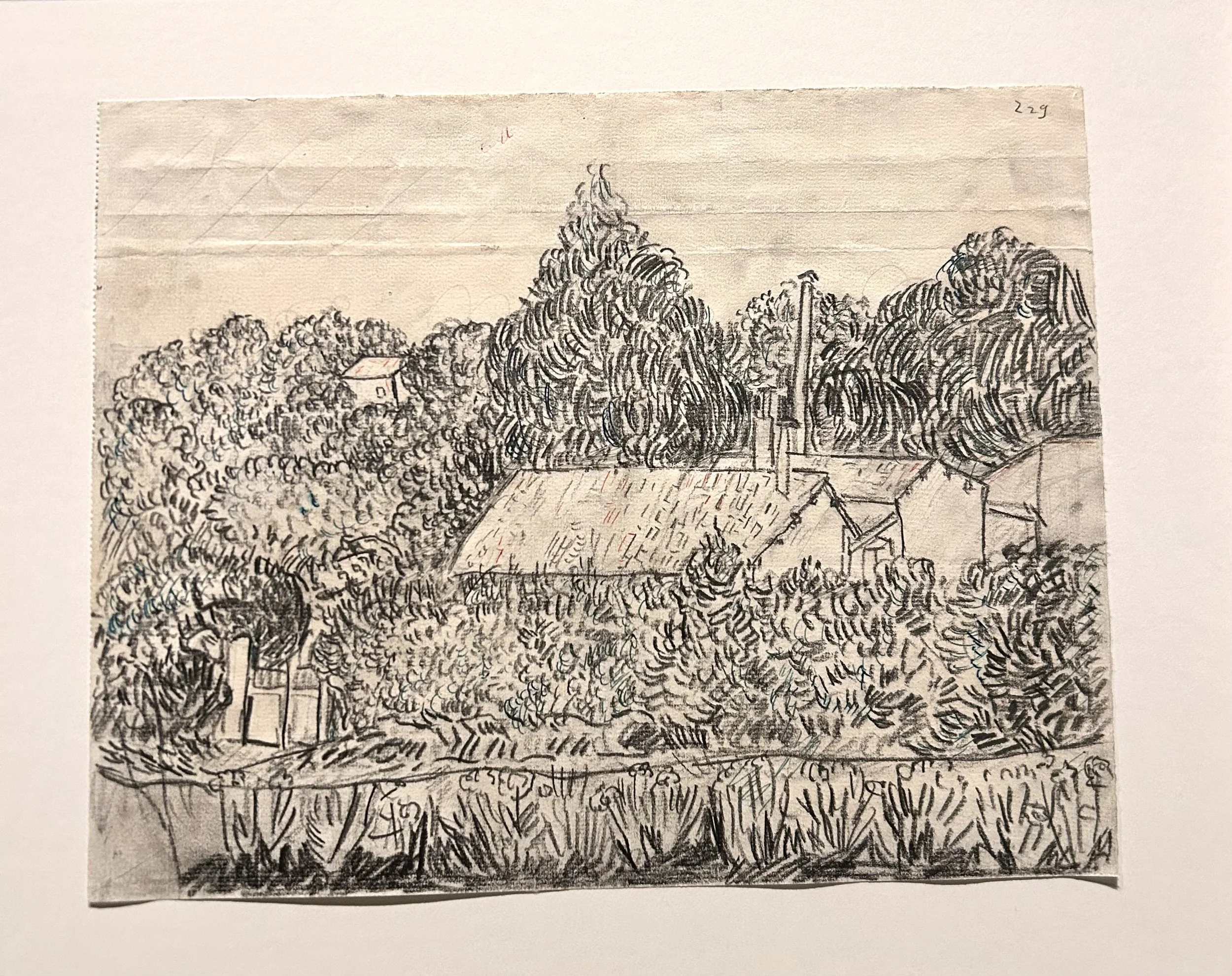

The cynical side of me thinks that the RA partly chose to showcase Kiefer alongside Van Gogh because the name ‘Van Gogh’ will inevitably bring people in. It was a bit of a tenuous link between the two artists beyond the fact that both painted in Provence and have used sunflowers in their work symbolically. Visually, I found that Kiefer’s dramatically scaled pieces very much overpowered the few Van Gogh paintings, which almost receded in this environment. For me, the most effective room curatorially, was the drawings. Here, we can observe sufficient comparisons between Van Gogh’s and Kiefer’s sketches, which were clearly direct references. This, for me, was the unsuspecting key which made it all make sense. When you see Kiefer’s starting point through drawings, it bridges the gap between the enormous works of apocalyptic devastation and Van Gogh’s vibrant oils.

Anselm Kiefer, Mr Dumont, (1963), Charcoal, ink and graphite on paper

Anselm Kiefer, Drawings of Provence, Charcoal on paper

Materials and Meaning

What struck me most walking through this exhibition was the sheer weight of Kiefer’s materials. Van Gogh’s paintings, despite layers of impasto and even at their most turbulent, are filled with light and have an airy energy – almost as though you are walking through wind. Kiefer’s works, by contrast, are heavy and almost feel oppressive. They look as though they’ve been naturally formed in the earth and dragged out, juxtaposing with the clean white walls of an austere institution. Lead, ash, straw and steel, stands as remains from the earth. They are not the carefully constructed brushstrokes of Van Gogh’s chemically precise mulled pigments. Van Gogh paints to elevate suffering into beauty, but Kiefer embeds the suffering into the pieces themselves.

Anselm Kiefer, Detail from The Crows, (2019), Emulsion, oil, acrylic, shellac, gold leaf, straw and clay on canvas

Why Now?

Both artists reckon with suffering and explore how the land can reflect our human emotion. However, I think that framing Van Gogh and Kiefer within the same exhibition is a curatorial strategy that encourages us to question the evolving role of the artist – particularly in times of crisis.

Kiefer’s artwork particularly resonates with audiences now. His works speak to historical trauma, to the brutality of war, genocide and to the human condition. It is shocking to see such poignant works, created in the aftermath of WWII, mourning the loss of life, when we are also living through a time of horrific warfare and injustice right now. Do we really learn from the past?

The exhibition presents to us these hard truths at a moment when we are again grappling with the same questions over and over. Our contemporary society faces uncertainty, fragmentation, and indeed, a disconnection with nature too. Thus, we can consider what we expect art to provide for us in these times.

Looking across the fields of Kiefer’s burnt ash, I wondered:

Where does the hope lie in this? Can we still find beauty, like Van Gogh does in his stars, amongst the sea of Kiefer’s destruction?

Exhibition running from 28 June - 26 October 2025 at the Royal Academy in London

Bonus Content!

Kiefer’s Flags (Art in Mayfair)

The RA has partnered with New West End Company for another edition of Art in Mayfair, with Kiefer exhibiting a series of flags which currently hang above Bond Street. They will be up until 22nd July 2025, timing to coincide with the RA’s Kiefer / Van Gogh exhibition.

The flags are designed with a sunflower motif inspired by Van Gogh. I wonder if this is another example of how Van Gogh is becoming ever-more commercialised. Kiefer was undoubtably inspired by Van Gogh, using the sunflower in much of his own practise to symbolise mortality and the cycle of life and death. This public display is a form of advertising for the exhibition in addition to providing colour and life to London’s West End, so everyone’s winning, right?

However, I worry about the over-commercialisation of artists like Van Gogh in our society. It is interesting to contemplate his legacy and how the artist would perceive his unbelievable success and popularity now. I was recently in Arles (in May 2025) and visited many of the locations connected with Van Gogh’s life and legacy. I was amazed at how much his suffering has become a huge money-making mechanism – even the asylum institution where he spent the final year of his life. His image in through his self-portraits are plastered across millions of fridge magnets, water bottles and socks, and his sunflowers are so iconic they’re almost cheugy. Contemporary artists can give consent, but for an artist, like Van Gogh, who is dead, it feels conflicting to manufacture a new, commercialised identity to his work.

Van Gogh socks for sale on Etsy

Does this even need a caption

Having said this, I love the idea of bringing art out of the exhibition space and into the public sphere. It is great to see the streets of London adorned with culturally engaging additions – and Kiefer is a great artist to showcase in our current climate. His work is so relevant to contemporary politics, and I am excited to see more of his new work soon, as he continues to be highly productive in his mature years. I will just be pleased when his sunflowers are not breathing the same air as designer brands and partially blocked by Rolex flags.