Fine Art or Functional Object? Picasso the Potter

Is it still just a plate if it looks back at you?

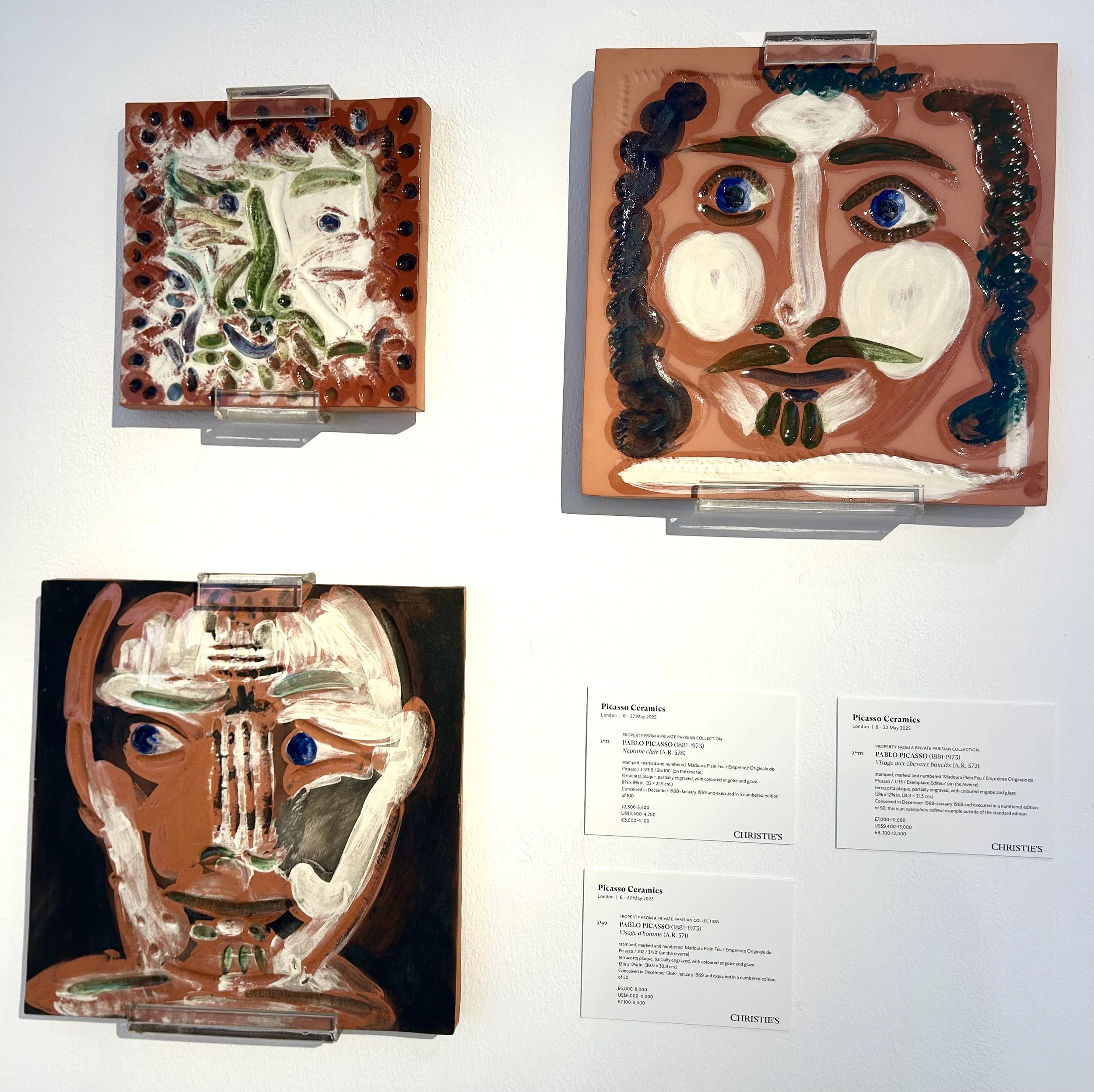

As a major auction of Picasso ceramics unfolds at Christie's in London this week (up till 22nd May 2025), it is tempting to simply view these pieces through the lens of market value. However, behind the catalogue numbers and price labels, lies an overlooked story about Picasso the potter: a contradictory symbol of radical reinvention and humour.

Exhibition display at Christie’s, London

Ceramics: Silly and Serious

Picasso’s ceramics challenge the monolithic narrative of Picasso as a champion of fine art, posing as a playful extension of his practice. These everyday objects are elevated by an injection of humour and spontaneity, with their evocative nature embodying the tension between fine art and craft. Though not entirely divergent from his Cubist works, Picasso’s work in clay offers a refreshingly subversive counterpoint to his persona of the tortured genius. Where his paintings often delve into politics, mortality and human suffering, his ceramics burst with vitality. Using animals as both a decorative tool and as a vehicle for expression, he fashions goats, owls and deer that frolic, stare and grin from their ceramic worlds. These objects are far from the solemn masterpieces carefully protected in the austerity of museums. These tactile objects are meant to be held, and indeed - enjoyed. The question is, what enticed Picasso to deviate in this direction?

From the late 1940s, these ceramics were created in collaboration with the Madoura Pottery Studio in Vallauris. They are a synthesis of technical innovation and a childlike playfulness, with Picasso embracing the charming irregularities of clay. He reimagined traditional dishes and vessels, augmenting the medium into new symbolic languages. With this ceramic series unsettling the boundary between high art and functionality or craft, it is interesting to ponder Picasso’s intentions. Was this a radical statement about the politics of media?

Pot-luck! Affordable Picasso?

Part of what makes this body of work so compelling is this historical accessibility. With many of the ceramics made in editions, more people could own a Picasso. In this way, they functioned as a form of artistic democratisation, welcoming high art into the domestic sphere. The nature of these multi-edition pieces is intrinsically less exclusive. This, combined with clay falling lower in the hierarchy of media than oil painting, has meant that these works are significantly more affordable than those hanging in major institutional museums. However, there is certainly an irony to be found: these "everyman" pieces are now sold in austere auction rooms for tens of thousands of pounds.

An example from the Christie's sale is Tete de chèvre de profil (1952). This plate features the profile of a goat's head, rendered with simplistic lines, almost like a lino or wood cut. Its playful composition evokes ancient European earthenware, whilst also embodying a modern, rebelliousness. Like many of Picasso’s ceramics, the plate questions boundary between art and object; art and decoration; comedy and seriousness; ancient and modern.

Human Imperfection in a Mechanised Age

There’s something deeply human about these works. In the wake of the Second World War, Picasso turned to clay, as a tactile, intimate, and even subversive response to post-war industrialism and disconnection. In a newly mechanised environment, he sought the immediacy of the hand-made and the rustic nature of earthenware. These ancient materials also reflect the mythological influences incorporated in many cases. However, the effect is not like a stoic Neo-classical glorification of ancient culture, but more of a romantic nod to simplicity of ancient civilisations. Many recurring motifs also allude to the humour.

What even IS painting anyway?

Art historically, these works have often been overlooked. Typically, they have been dismissed as either simply decorative or secondary to his impressive paintings. But that hierarchy is becoming challenged more and more. As contemporary artists continue to blur media boundaries, Picasso’s ceramics feel present in these questions: where does art end and craft begin? How do we value the different surfaces which paintings can inhabit? What even constitutes as a painting?

We are left pondering – how will the values of these ceramics be valued differently as our perception of ‘high art’ morphs with each generation’s trends and philosophies? Perhaps they are exemplary of the fact that art doesn’t always have to suffer to be serious, nor be overtly political to make it to the history books. High-value art can just be a wide-eyed owl on a pot, or a magical goat-plate. Within the gravitas of auction houses and tense bidding wars, let’s not forget Picasso’s humour.